At times during Raelene Boyle’s passage through Australian Olympic history, events seemed to conspire against her. In a 14-year international career which established her as a worthy successor to the great sprinters Marjorie Jackson, Betty Cuthbert and Shirley Strickland, she really deserved to have won Olympic gold. Instead, she had to settle for three silver medals and a medley of frustrating memories.

At the 1972 Munich Olympics, she was beaten twice into second place by an East German athlete whose credibility was later stained by allegations that she had been part of a systematic doping program. And four years later, in her target event at the Montreal Olympics, the 200 metres, Boyle was disqualified after being ruled guilty of two false starts. Film footage later demonstrated that she hadn’t jumped the gun in the first of them.

Raelene Boyle shed a few tears at times like these — but then she always got on with her glittering career. The truth is that she was one of the most resilient characters to have graced the Australian track and field scene. She was always a fighter, possessed of an irrepressible, larrikin spirit that somehow equipped her to bounce back from the harsh and varied setbacks that afflicted her. It was a spirit that would come to her aid long after her running career had ended when cancer invaded her body.

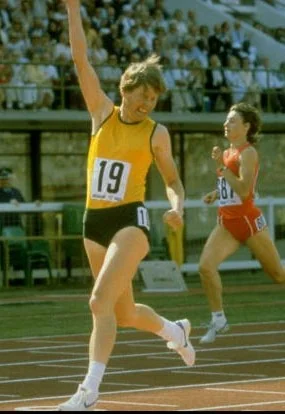

The last race of that career was one to savour: she won the 400 metres at the 1982 Brisbane Commonwealth Games, then embarked on a victory lap that left no doubt about her place in the affection of most Australians. Apart from those three Olympic silver medals, she took with her into retirement seven Commonwealth gold medals and a burning, justified conviction that at her peak she had been the fastest drug-free runner in the world.

It was in the summer of 1968 that Boyle appeared suddenly on the athletics scene as a 16-year-old amateur, equipped with natural, explosive pace and a technique more mature than she was. She was coached mainly by her father, who owned a bike shop near their home in Coburg, Melbourne — with extra instruction by correspondence and during holiday stints in Perth from a former professional sprinter, Les Jamieson. It was a bike-riding family, and her brother Ron later represented Australia as a sprint cyclist at the Montreal Olympics.

At the Adelaide national championships, she qualified for sprints at the 1968 Mexico City Olympics, where she finished fourth in the 100 metres — missing out on a bronze medal in a photo finish — then won silver in the 200 metres. The woman who beat her in that race, Poland’s Irena Swezinska, was one of the enduring champions, a woman who later equalled Strickland’s record tally of seven Olympic medals.

It was during those Games of 1968 when Boyle had not long turned 17, that Jesse Owens, winner of four gold medals at the 1936 Berlin Olympics, watched the young Australian sprinter in action and offered the opinion: “I have not seen a girl so beautifully balanced.”

Balanced she was on the track, but there were some rough edges to the youthful Raelene — some of them uncannily reminiscent of the early Dawn Fraser. As a little girl growing up close to Pentridge Jail, she hated wearing dresses, loved beating up boys, knocked around with her brothers Rick and Ron, played street cricket with rubbish-tin wickets, and swiftly learned to swear with flair. She was a natural non-conformist with a stubborn streak, and she quickly developed an aversion to over-zealous administrators.

Amateur officialdom was never too tolerant of rebels, whatever their talent — and Boyle found herself in trouble for all kinds of alleged misdemeanours. Just a few of the accusations against her were that she looked over her shoulder during races, grabbed the finishing tape with both hands, walked barefoot in inappropriate places, wore frayed jeans, ran backwards in competition, swore after a race and failed to wear her registered number. Of course, she also happened to win often.

She was reprimanded, even suspended — but never subdued. Ever defiant, never diplomatic, she once took to wearing a bright-red T-shirt emblazoned with the words: I RUN FOR FUN.

For all her speed on the track, Boyle never quite got her timing right. First, she made a professional commitment to sport in the days of amateur rewards. More importantly, though, her athletic career peaked just when the East German corruption of the sport, via steroids and other drugs, was turning out an assembly line of female swimmers and runners with huge shoulders, abundant body hair and incredibly muscular thighs and calves. Her exposure to that world came at the 1972 Munich Games, when she was beaten into second place in both sprints by East Germany’s Renate Stecher, who was later proved to have taken part in the doping program.

In her recent, deftly sub-titled memoir, RAELENE: Sometimes beaten, never conquered (written with Garry Linnell), Boyle recalled evocatively her uncontrollable sobbing on the dais at the medal ceremony. “It’s a strange feeling to look back …,” she wrote. “That girl with tears in her eyes standing with a silver medal around her neck is a completely different person … If I could, I would love to reach back through time, put my arm around her shoulders and tell her not to worry about it. Look at you, I would say. You’re 21 years old and you are the fastest non drug-taking athlete in the world. You are still Australia’s only track and field medallist at these Olympics. In fact, you will be the country’s only medalist on the track between 1968 and 1980.”

Boyle’s misfortune over the start of the 200 metres semi-final at her next Olympics, in 1976, owed something to a Canadian starter’s erroneous conviction, and more to her own feisty, even garrulous nature. The starter believed she had moved while in the “set” position, although later film evidence did not substantiate his ruling.

Her own belief was that something behind her had moved, and caught the starter’s eye. The second call against her, which erased all hope of taking part in the race, came after she decided — while the field was again locked at “set” — to make a personal protest.

“I wasn’t starting,” she explained later. “I was coming off the mark to discuss the matter with him. I didn’t realise until just before I got on the mark that it was I who’d been given the break. I wanted to say to him, ‘Hang on, I didn’t break then.’ I just rolled off the mark, and the gun went. Then it all sank in, that it really was a start, and I should have had my mind on the job.” The simple truth, of course, was that her concentration had been shattered.

In 1996 Raelene Boyle was diagnosed with breast cancer, and a few years later with ovarian cancer (twice). In her serial battles against the disease and the moods of depression that have accompanied it, her bluntness, honesty and sheer bloody-minded determination have served her well. It was through her own battle for survival that she discovered a new passion.

As she wrote in her book: “I began to understand that because of my public profile I could play a role in helping other women — and men — confront and overcome some of the hurdles placed in front of them when encountering cancer.” She has become something of beacon, travelling the country and identifying with such bodies as the Breast Cancer Network and the Sporting Chance Cancer Foundation, trying to raise funding and awareness. She has made the battle against cancer a personal mission. “I’m tired of the toll and the anguish and the grieving that cancer leaves in its wake,” she wrote. “And yet it is a battle I know I must face and fight every day for the rest of my life. More often I win. But there are hours, sometimes days, when I lose. The key, though, is never to surrender.”

That last sentiment, of course, summed up the Raelene Boyle way.

1968 Olympic Games, Mexico

Silver medal 200m

1972 Olympic Games, Munich

Silver medal 100m

Silver medal 200m

1970 Commonwealth Games, Edinburgh

Gold medal 100m

Gold medal 200m

Gold medal 4x100m relay

1974 Commonwealth Games, Christchurch

Gold medal 100m

Gold medal 200m

Gold medal 4x100m relay

1978 Commonwealth Games, Edmonton

Silver medal 100m

1982 Commonwealth Games, Brisbane

Gold medal 400m

Silver medal 4x400m relay

© Harry Gordon, 2004. Provided courtesy of the author and not to be used elsewhere without permission.